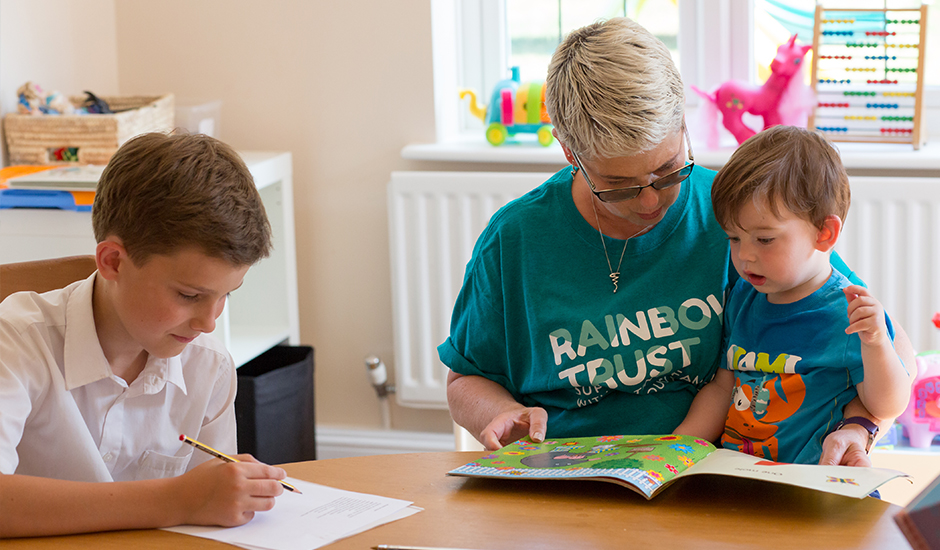

There’s never a good time to discuss illness or death, but there are ways to ensure children feel they can ask questions and cope with bad news. Anne Harris, Director of Care Services at Rainbow Trust gives some advice here on having difficult conversations.

“Am I going to die?”

You are driving home, concentrating on the road, when your child suddenly asks, “Am I going to die?” This is not a question any parent will ever want to hear but if your child has a serious illness they may ask it when you are least prepared. So what is the best way to respond?

Give as full a picture as possible

The first difficult conversation you may have is when your child becomes sick. “A parent’s instinct is to protect their children from anything bad,” says Anne. “But children have an immense capability to cope. We advise families to be honest and to give as full a picture as possible.”

Keep hope alive but be realistic

Whatever conversation you are having, it is vital to let your child ask as many questions as they want. “No one has all the answers so if you don’t know then say so. Tell them you’ll try and find out. And don’t make promises you can’t keep,” suggests Anne. It also helps to find a comfortable time and place to talk. “I think it’s no coincidence children often instigate difficult conversations in the car when adults can’t look at them,” says Anne. “Children think they can catch their parents off guard. Equally don’t bamboozle them with big words or euphemisms,” she adds, emphasising “how it’s important not to talk about people ‘going to sleep’ or you’ll never get a child back in to bed!”

Parents naturally never want to be in the position of having to tell their children they’re going to die and Rainbow Trust’s philosophy is ‘keeping hope alive but being realistic’. However, if a child asks if they’re going to die, Anne suggests finding out what the child already knows and then following their lead by being honest and this conversation might therefore be something like, ‘You know we said you’d have treatment to try and make you better. Well, although everybody tried really hard, the treatment hasn’t worked. Sometimes when people can’t get better it means they’re too poorly to be able to stay alive.’

Don’t forget siblings

It is also important not to forget siblings. “Parents can underestimate a brothers or sister’s belief that they caused the illness,” says Anne. “You should make it clear that’s not the case.”

Let them know you will always, always love them

“Finally, it helps to let everyone know it is OK to be upset and to express your own sadness,” advises Anne: “Whatever conversation you have, you need to let children know that they’re loved and that you will always, always love them – whatever happens.”